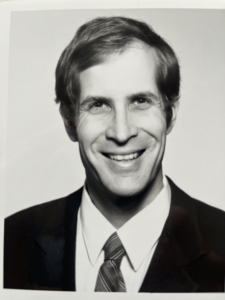

Eric Udd serves as a strategic committee member of the IEEE Photonics Society Industry Engagement Committee and holds the position of President at Columbia Gorge Research.

Below is a brief Q&A session with Eric, offering insights into his background and aspirations as a prominent figure in the fiber optics industry.

What is your current profession and technical area(s) of interest?

I am serving as President of Columbia Gorge Research, and have been extensively engaged in the realm of fiber optic sensors since 1977. During my tenure at McDonnell Douglas spanning from 1977 to 1993, I oversaw the management of more than 30 DOD, NASA, and internally funded fiber optic sensor initiatives. Progressing through various roles from Engineer/Scientist to Unit Chief, Manager, and finally Senior Staff Manager-McDonnell Douglas Fellow, I demonstrated a comprehensive understanding of the field and its applications.

What was your “Photonics Moment”? Why did you decide to pursue this field?

My fascination with optics began at an early age, around 9 or 10 years old, when my interest in astronomy and planets took root. By the time I was around 10 or 11, I felt compelled to construct my own telescope. With my father’s approval, I embarked on the project, but there was a condition: I had to grind a mirror myself. The mirror I crafted was about 6 inches or roughly 15 centimeters in diameter. It took me several months to achieve the precise curvature needed for optimal performance. This endeavor taught me not only about the principles of optics but also the practical skills required to assemble a functional telescope.

My passion for aerospace was equally strong from a young age. The opportunity to merge my interests in optics and aerospace, particularly space exploration, felt like a dream come true. However, my journey into fiber optic sensors was initially sparked by the Delta rocket program’s quest for improved guidance systems. The program had devised a cost-effective yet high-performing method for guiding the Delta rocket into orbit. Concerned about potential technological advancements by competitors, they tasked the electro-optics lab with exploring alternative gyroscopic systems and I was appointed to lead this endeavor.

When you started your first company, you had 15+ years of industry experience and a strong professional network. Would your approach to starting a company have changed if you started earlier in your career? Do you have any advice for young aspiring entrepreneurs who may have innovative ideas but less industry experience?

Utilizing the approach I employed for my first company early in my career would have posed significantly greater challenges. At that time, I lacked the necessary financial resources, experience, and a robust professional network. Moreover, I lacked the motivation to depart from my job role at McDonnell Douglas.

Starting a company earlier would necessitate careful consideration of various factors: (1) Ensuring adequate financial resources for at least four to five years, which may involve securing loans, partners, or angel investors, particularly challenging in areas lacking technical support and investment opportunities. (2) Assessing the availability of a comprehensive technical and business skill set, and exploring avenues to acquire or supplement these skills through hiring, partnerships, or investments. (3) Evaluating the development timeline for building a professional network and acquiring high-potential customers, and considering partnerships or investments to expedite this process.

In summary, I would recommend either waiting until your skill sets, networks, customer base, and financial resources are sufficiently developed for a higher chance of success, or seeking partners or investors to fill in the gaps.

Starting an R&D organization could be challenging provided that your country’s government would give start-up resources and funding. How did you mitigate the challenges of receiving funding or working with government organizations?

During my tenure at McDonnell Douglas in the United States, I gained exposure to aerospace and defense funding agencies such as the Air Force, Navy, Army, DARPA, DOE, and NASA, as well as limited exposure to the oil and gas sector during the late 1970s/early 1980s energy crisis. Engaging extensively in proposal preparation, contract management, report generation, and customer interactions with these organizations proved advantageous, given their control over approximately half of the US R&D budget. Moreover, Congress mandated that 2% of their R&D budget be allocated to small businesses through the Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) Program. I capitalized on this by partnering with major corporations like Boeing, Schlumberger, and Thiokol/ATK/Orbital ATK/Northrup Grumman to secure early contracts. My initial significant success as a small business came from a contract awarded by NASA Langley, with key partnerships involving Sandia Livermore National Labs and Stanford. Prior to this, I undertook smaller projects for Sandia Livermore and collaborated with an established composite company, Production Products, in support of bids to DARPA. The risk associated with venturing into entrepreneurship can be mitigated through customer recognition, leveraging transferable skill sets from large businesses, and establishing networks and connections based on past performance.

What are the challenges of switching from Sole Prop to LLC to S-corp as the organization grows over the years? Is it recommended to start small like LLC and then switch to S-corp?

Rules govern the transition from Sole Proprietorship to LLC to S Corporation, ensuring the government maximizes tax collection during the switch, overseen by the IRS in the US, often managed by a CPA firm, as in my case.

The choice of where to begin depends on individual circumstances. For sole investors, starting as a Sole Proprietorship may suffice for low-risk ventures, but I recommend a sole owner LLC for added protection at minimal cost. Alternatively, if there’s a partnership, starting as an S Corporation or a C Corporation (Business Name Inc.) is an option. Each approach carries significant tax implications, necessitating a comprehensive understanding before deciding. Consulting with a CPA firm or studying business literature on the topic is advisable, especially for partnerships or external investors. With careful planning, it’s possible to structure the business to maximize tax benefits for investors, potentially extending the payback period for technologists.

Given your long and successful track record for establishing a small business, what would you have done differently either from a technical/market or business/sales perspective?

In hindsight, I would have structured my first company differently and paid closer attention to the business advice provided by a CPA. Interestingly, the structure recommended by the CPA ultimately favored the CPA firm rather than benefiting the business itself.

Did you consider venture capital funding when starting your business?

No, during my time at McDonnell Douglas, I was approached by venture capitalists regarding the possibility of starting my own business, but I declined their offers. Reflecting on those conversations, it became evident that they were primarily interested in establishing their own business and marketing managers, with me providing the products. It wouldn’t have truly been my own company, although I would have been incentivized by having partial ownership.

If an industry is capital-heavy (like semiconductor manufacturing rather than IC design), is it not an appropriate start-up target? Or is there a strategy to finally achieve that?

If I understand correctly, if the question is whether targeting a capital-heavy industry as a small startup is feasible, my response would be twofold. Firstly, no, unless you possess a groundbreaking approach to revolutionize such an industry, I wouldn’t recommend attempting it. Elon Musk managed it with SpaceX, but it required nearly $100 million in seed funding and almost led to bankruptcy. Industries like semiconductors can be particularly challenging to break into. However, yes, if you’re referring to developing a product that enhances the industry, there are examples of success. For instance, a local fiber sensor company created a fiber optic temperature sensor based on blackbody radiation, widely adopted by Intel, resulting in a sale of approximately $30 million in the mid-1990s. Many of my own inventions aimed at improving the products of well-capitalized commercial companies, forming the foundation for both of my ventures.

What’s your major focus? Product development or customized sensors based on a customer’s needs. For the latter, how would you arrange the intellectual property of your development?

For both of my companies, my approach began with identifying customer needs. Then, I evaluated whether I could devise a superior fiber sensor solution in terms of both performance and cost compared to existing options. Some solutions addressed unmet needs with no competition, while others faced existing alternatives. I focused on developing products with significant performance and financial advantages, which isn’t overly difficult if the potential is evident. However, if a competitor already offers a similar solution, attempting to catch up is futile; it’s better to seek alternative opportunities. The products my companies developed were cutting-edge, with the first company catering to a diverse customer base and the second focusing on customized products for established entities.

Regarding intellectual property, I patented and developed my own inventions. Although I attempted to license government-owned inventions a couple of times, the bureaucratic process was arduous, resulting in financial losses and wasted time. As a result, I never pursued this avenue again.

How did you acquire employees? How do you motivate researchers or staff to join a “shaky” venture rather than a stable job? Would you suggest low-cost part-time workers?

I refrained from hiring employees until securing a two-year contract from NASA, ensuring confidence in doing so. Instead, I trained individuals within collaborating companies and organizations to assist as needed. My initial hires came from Oregon State University and the Oregon Institute of Technology. With the support of a University of Portland professor, Bruce Ferguson, I obtained the NSF grant to conduct hands-on fiber sensor training for professors in the Pacific Northwest. This initiative, hosting about ten professors from Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana, aimed to equip them with practical skills and tools. I actively supported these universities by serving on advisory boards, directing funding their way, and seeking recommendations for top students.

To attract and retain talent, I offered competitive salaries and benefits, emphasizing professional growth opportunities. As the company expanded, I began hiring a mix of experienced professionals and recent graduates, receiving around ten applications per position. To foster employee development, I facilitated conference attendance, direct customer interaction, and involvement across various business functions. Transparency regarding the company’s financial and technical aspects ensured everyone felt engaged and informed.

At an early-stage startup, you have limited capital/cash compared to the big organizations for salary/benefits to the employees. How do you hire and retain good technical employees in such a case?

My initial hires were funded mostly through government R&D program wins, supplemented by increasing product sales cash flow. Most hires came with strong personal endorsements, and every serious candidate underwent company-wide interviews. We prioritized employee growth, fostering numerous research and development initiatives aimed at advancing technology and addressing key technical challenges. Prompt patenting and publication of innovations ensured employees gained recognition, with many presenting at conferences. Even those not directly involved in publishing or inventing attended conferences, engaged in papers, and interacted with customers.

Do you consider contingency in addition to overhead in your proposals? If yes, at what percent?

For government contracts where our company retained intellectual property rights, we aimed for a 5% profit on cost plus fixed fee contracts, with funding strictly limited. Commercial contracts had higher baseline rates and profit margins. Our charges were influenced by the alignment of the research with our goals and the potential to retain patent rights in less relevant fields for the customer.

What are the implications of the work for the industry as well as the benefit of humanity? What are your thoughts on Social Entrepreneurship? (i.e. an entrepreneurial approach in which companies develop, fund, and implement solutions to aid social, cultural, or environmental issues.)

I’ve contributed to fiber sensor projects spanning aerospace, defense, oil and gas, civil structures, medical, environmental, and electric power sectors. Initially, aerospace, defense, and oil and gas sectors drove much of the research, with later diversification into civil structures, medical, environmental, renewable energy, and electric power applications.

In the US, government R&D funds, primarily allocated to aerospace and defense, heavily influence initial research directions. Subsequently, commercial sectors like civil structures, medical, environmental, renewable energy, and electric power enter the scene, driven by market opportunities and regulatory requirements.

The fiber sensor technology I’ve worked on finds applications in commercial and military aircraft, interplanetary rockets, missiles, and mitigating oil operation hazards. It supports surgical procedures, health monitoring for infrastructure, and environmental surveillance. Funding for research and development is typically driven by government customers and large corporations seeking tailored solutions for their products.

Why do you think Mentorship matters, especially in the industrial, entrepreneurial, and/or start-up space?

Retaining employees hinges on providing opportunities for their development, necessitating comprehensive mentorship. Small companies and startups have the advantage of involving everyone in various aspects of the business, fostering teamwork and collective problem-solving.

Initially, I mentored the first few recent graduates I hired. As the company expanded, I selectively brought on experienced employees recommended by mentors, maintaining a ratio of about three or four to one. This approach proved successful, as the mentors’ diverse expertise complemented the enthusiasm of new graduates, who eventually evolved into mentors themselves.

Beyond the vital importance of fundamental discoveries, Photonics is, by definition, an applied science. What emerging technologies or breakthroughs in photonics and optics do you think society should invest in and focus on more?

Optics and photonics profoundly impact our lives through LED lighting, solar cells, telescopes, fiber optic communication, laser diodes, imaging systems, and spectroscopy. Light serves as a primary tool for sensing, manipulating, and understanding our world. Advancements in atto-second lasers, quantum computing, and entanglement hold promise for pioneering new technologies and products. I anticipate optics and photonics will remain pivotal across Earth, our solar system, and beyond for generations to come. Witnessing the remarkable achievements in this field during my lifetime has been awe-inspiring, and I foresee this trend continuing.

Determining societal investment priorities hinges on each society’s unique goals and needs. Investments are directed toward photonics and optics solutions that align with these objectives.

However, humanity faces the challenge of diverse societies with often conflicting goals, where technology can either alleviate or exacerbate issues.

To set meaningful goals, entrepreneurs must reconcile what they want with what they are willing to risk. Have you ever faced such doubt or imposter syndrome in pursuing a business venture?

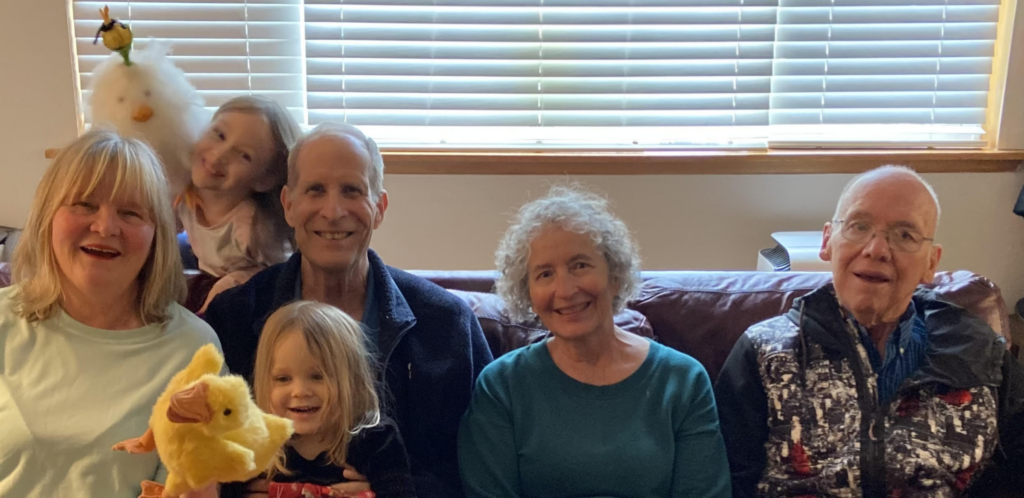

My approach to growing a company has been conservative, navigating financial risks with mixed outcomes, yet ultimately providing a livelihood, supporting my family, and contributing meaningfully to the fields of fiber optic sensors and smart structures. Many colleagues I’ve collaborated with have made significant contributions, and I believe I’ve aided many more, benefiting greatly from others’ support and encouragement. While I’ve never experienced imposter syndrome, my upbringing emphasized doing my best, a philosophy that has served me well. Reflecting on my journey, I’ve encountered challenges, successes, and setbacks, driven by effort, decisions, and a willingness to push my limits. I draw inspiration from my grandparents’ resilience and resourcefulness, despite limited formal education, finding pride in their ability to make the most of what they had.

Engineering professionals tend to focus heavily on the technical aspects of the product. It’s what gets us excited. Could this be a shortfall? What advice do you have on balancing business strategies and marketing principles with your technical expertise?

I believe before embarking on any technical project, the most crucial consideration is to assess if the proposed solution offers (1) a significant performance advantage and (2) financial viability that goes beyond mere improvement. Without these factors, the solution may remain unused, necessitating a reevaluation of the project’s direction. Pursuing technology without clear objectives is inefficient and unlikely to generate the income required for a company’s survival. When unsure, revisiting these two criteria is essential. Furthermore, for success, a company’s technical goals must align with its own resources as well as those of its supporting end users.

Tell us something fun about yourself:

Here are a couple of fun facts about me: I’ve been running marathons for around 14 years, and the third edition of the Fiber Sensor book was released. Additionally, I have five grandchildren, including twins (7 months old). I love spending time with my grandchildren, hiking, delving into family history, and collaborating with individuals from Finland to support optics research.